Tiny Homes for the Homeless: A Student Design Challenge

As architects of PK-12 educational facilities, one of the most illuminating things we can do is spend time in classrooms, observing or—better yet—participating in teaching and learning. So when Mike Wierusz, an educator at Washington’s Inglemoor High School and long-time collaborator with NAC Architecture, asked us to help him and his Sustainable Engineering & Design students we jumped at the opportunity.

The project centered on designing to address homelessness. The class partnered with local nonprofit Sawhorse Revolution, which engages students through design and carpentry, and local contractor Blue Sound Construction. The design prompt was to develop a Tiny Home Village for the homeless, with dozens of 8'x12' sleeping cabins surrounding communal gardens, a kitchen, a dining tent, and toilet and shower facilities. The village is expected to provide shelter, access to services, and support community-building for its residents.

Mike Wierusz and his students spent a day visiting established homeless encampments throughout Seattle, including Interbay’s Tent City. Photo Courtesy of Shane Harms

For Mike, selecting this project promotes a broader vision of sustainability, which engages students with tangible relevancy. He explained, “Sustainability is a big part of the curriculum. On a global level, there are the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.1 And then on the local level, there is a continuous presence of homelessness in the media, and even as we drive around town. Every year I try to find an authentic ‘think globally, act locally’ problem to focus on, and homelessness made sense. I always try to build my projects around industry partners and I had connections to Sawhorse Revolution, who connected me with the Low Income Housing Institute. It helped to know that Sawhorse Revolution had presented at a conference in combination with NAC Architecture. We've worked [with NAC] and it would be a professional endeavor for the students.”

Gaining Context

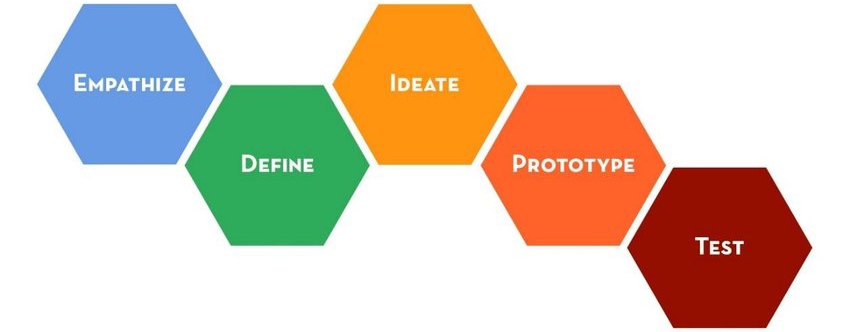

The Stanford d.school Design Thinking Process (Stanford d.School 2010, p.6)

As a framework to help students approach complex problems like designing a Tiny Home Village, Mike teaches the Design Thinking process as defined by the Stanford d.school.2 This process began by asking students to “empathize” with the homeless served by Tiny Home Villages. To develop this empathy, the class took a field trip to five established encampments, where tours were led by one of the tenants. Mike thought these tours were a successful component of this project, bringing students in direct contact with the people they were designing for. “It’s easy to think, ‘oh, 12,000 homeless, out of a population of half a million, what does that mean?’” said Mike. “But I think the field trip really made us see that it's 12,000 individuals who are on the streets. These are real numbers and real people.“

Mike went on to describe one particular moment that stood out. “One of the people touring us around, right at the end of the field trip, found out we were from Inglemoor High School. And she said, ‘Oh, I went to Inglemoor.’ That's a pretty strong thing. You are taking a field trip and there is someone who went to the same school as you, struggling for one reason or another to be able to stay in a house. It was a huge empathy piece.”

Planning the Tiny Home Village

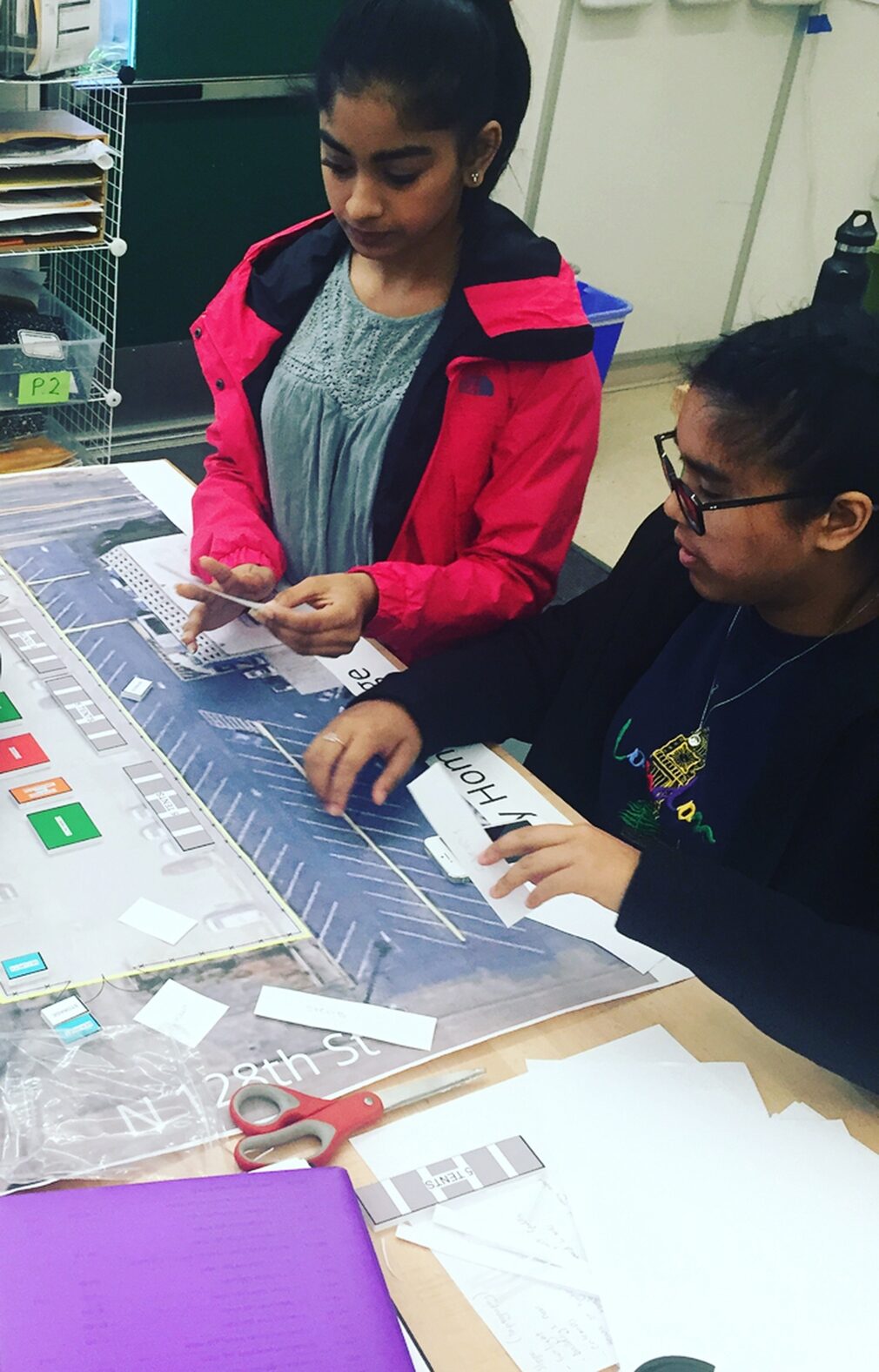

Back in the classroom, Brian kicked off the “ideate” step in the Design Thinking process with a presentation on site planning, introducing students to the fundamentals of site analysis and questions to consider as they planned the Tiny Home Village. He gave the students enlarged satellite photos of the proposed site and scaled blocks representing the program components, which Mike says brought a level of authenticity to the project. He explained, “To create the site planning materials that Brian bought in, with the schedule and the resources we have on campus, would have taken me at least a week. So having it all brought in, working with professional manipulatives, was hugely impactful. It was not just your expertise, but providing them the tools that you guys would use.” Brian led the students in a site planning exercise that emphasized quickly prototyped site plan options for the Tiny Home Village. Students often want to polish their first idea, but this makes it hard to ideate in a plastic way when the first idea encounters challenges.

After the students had developed their site layouts, Philip joined the class for the “test” step in the Design Thinking Process: a review and critique of their work. The level of thought they had put into the layouts was impressive; the students considered services, street appeal, privacy, and fostering a sense of community. To introduce the next step, Philip presented an overview of the principles of building design, covering both exterior and interior design, responding to climate, expressing structure, experiential design, and reinforcing a sense of dignity for this marginalized population. Later, he returned to work with the students as they developed their design for the tiny cabins. Although the means were limited by necessity, the students were able to consider a wide range of choices, and the impact of these on inhabitants, throughout the design process.

Students collaborate on developing a site layout for the Tiny Home Village.

Brian Love worked with Mike’s Sustainable Engineering & Design students on site layout. Photo courtesy of Mike Wierusz

Brian Love worked with Mike’s Sustainable Engineering & Design students on site layout. Photo courtesy of Mike Wierusz

Philip helped review student designs for the Tiny Home cabins.

It’s a Win-Win Situation

What makes this type of learning program work? Mike says that an important aspect is having relationships with professionals in the industry. “It just makes it real, you know? You do this every day. I do it year after year, but every year I have a new crop of students who perhaps have not even met an architect. They have never sat down side by side and watched how an architect thinks through a problem. It’s about giving the kids authentic experiences with professionals, which is priceless and should be highly sought after in every classroom.”

For NAC, the opportunity to interact with Mike, and directly with the students, allows us to put ourselves in the teacher’s shoes, and collaborate with students who are completely engaged in project-based learning. This helps us to really understand what works in an educational space and how students use their environment to learn, which in turn informs our PK-12 project designs. Also, this interaction helps remind us of how essential each step is in the Design Thinking process. One can’t shortchange a step without limiting the potential for all the efforts that follow. Needless to say, the benefits of volunteering some time in a classroom are realized by everyone involved.

References

1 https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ sustainable-development-goals/

2 https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/ the-bootcamp-bootleg

Mike Wierusz is an educator at the Northshore School District’s Inglemoor High School. His courses focus on sustainable product, building, and system design, with a mission to develop sympathetic and curious visionaries who continue on to make a positive contribution to the world. Mike was named a 2014 Allen Distinguished Educator by the Allen Institute. Learn more about Mike. Mike is a long-time collaborator with NAC. See a video and learn more about some of our previous projects together HERE.

Sawhorse Revolution is a Seattle-based non-profit whose mission is to foster confident, community-oriented youth through the power of carpentry and craft. Learn more about the organization.