Supporting Students to Thrive: Part 1, A Mental Health Check In

In October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics declared a national emergency of child and adolescent mental health, citing the rates of childhood mental health concerns.

“We are caring for young people with soaring rates of depression, anxiety, trauma, loneliness, and suicidality that will have lasting impacts on them, their families, and their communities,” (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association, 2021).

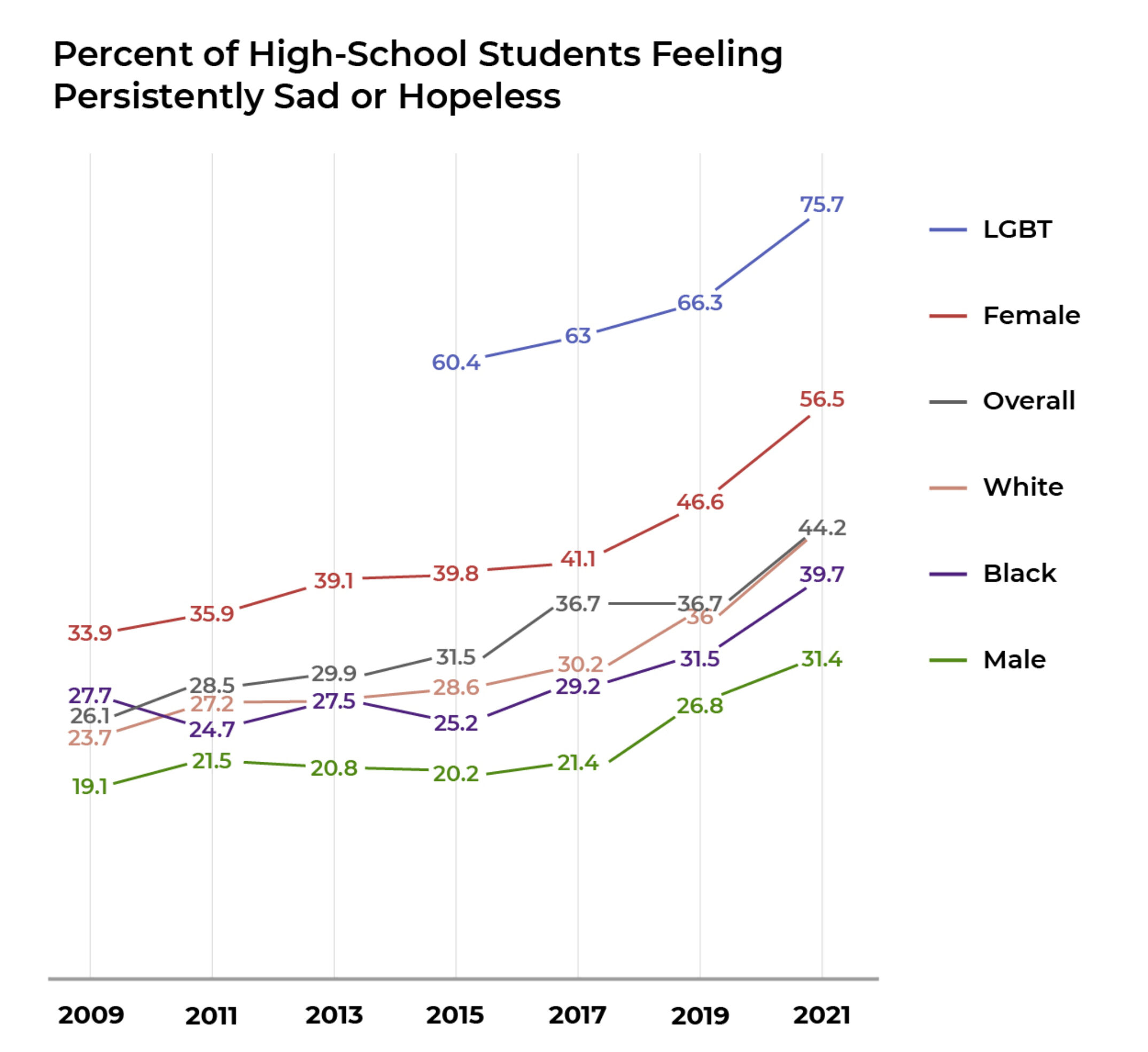

Data gathered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2009 – 2019.

Mental health issues manifest themselves in a variety of forms such as anxiety disorders (OCD, PTSD, social phobias, and generalized anxiety), eating disorders, mood disorders, and behavior issues that can cause harm to oneself, and to others. They can also exacerbate challenges faced by neurodiverse students, such as those with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and autism. If left untreated, these are likely to persist and are associated with problems in adolescence and adulthood, including impaired social functioning, suicidality, substance misuse, criminality, lower educational and occupational attainment, and lower quality of life.

In addition, evidence indicates disproportionate effects on students based on factors such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender, disability status, and sexual orientation. These disproportionate outcomes are influenced by factors such as bias, racism, and school policies. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s report, Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs (2021), black teens have a disproportionately higher rate of suicide compared to white teens. In early childhood education, there is evidence that suspension and expulsion practices disproportionately affect young boys of color. This trend continues into the elementary and middle school setting causing youths of color to have poorer outcomes compared to white peers.

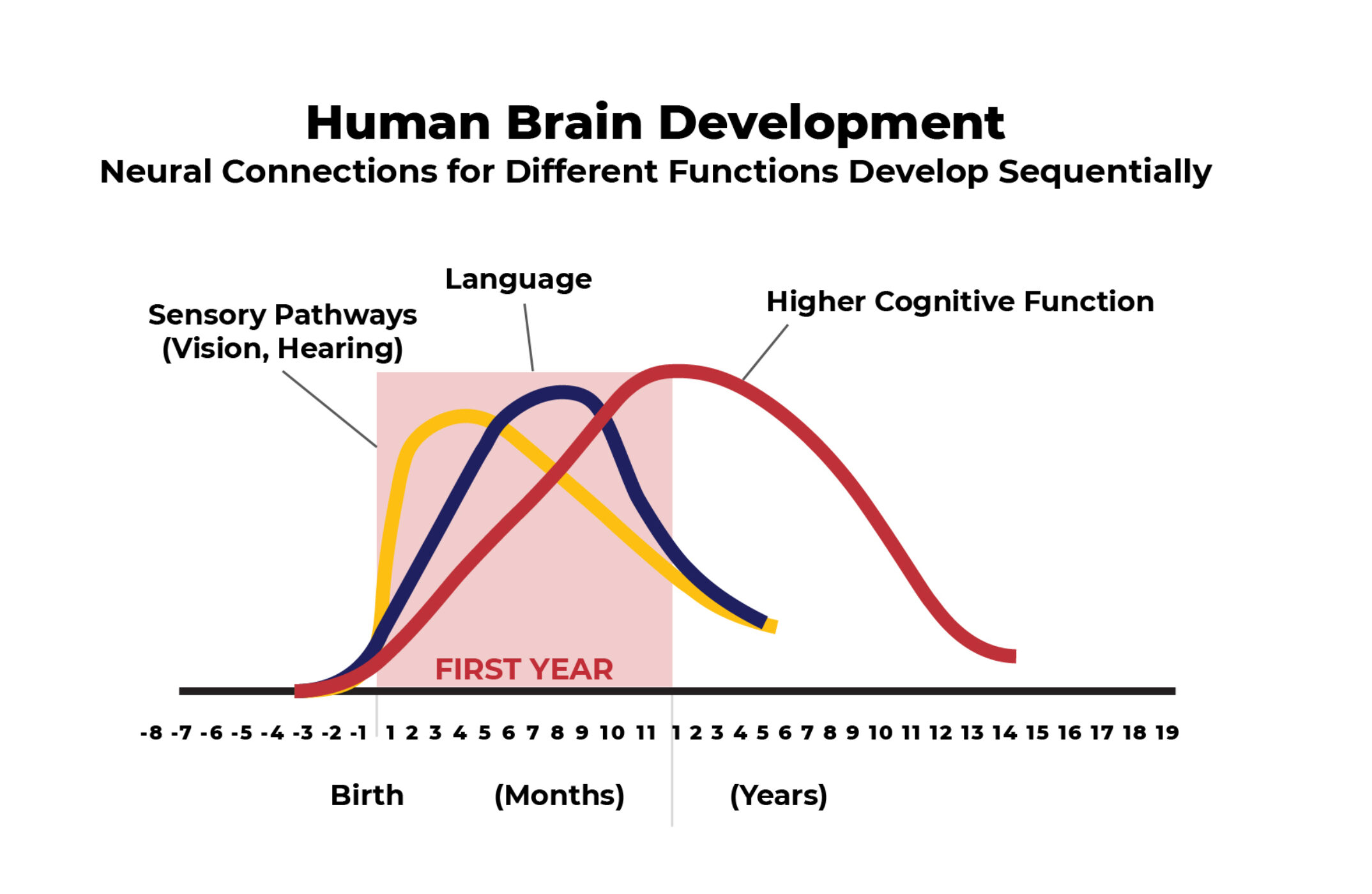

In the proliferation and pruning process, simpler neural connections form first, followed by more complex circuits. The timing is genetic, but early experiences determine whether the circuits are strong or weak. Data Source: C.A. Nelson (2000). Credit: Center on the Developing Child.

Our brains undergo significant development during the formative childhood and adolescent years, establishing neural pathways that have lasting effects throughout an individual’s life. When considering youth mental health, NAC reviewed studies of brain development to understand the various phases and best ways to support healthy growth. Research, such as that of C.A. Nelson (2000) shown in the graph above, clearly shows the first five years set the stage for lifelong success in school and life. When a child experiences a supportive environment during their early years where their basic needs are met, along with age-appropriate stimulation and care, this is an optimal setting for healthy brain synapses’ development. Toxic stress from ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) can negatively affect children's brain development, immune systems, and stress-response systems. “These changes can affect children's attention, decision-making, and learning. Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships,” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

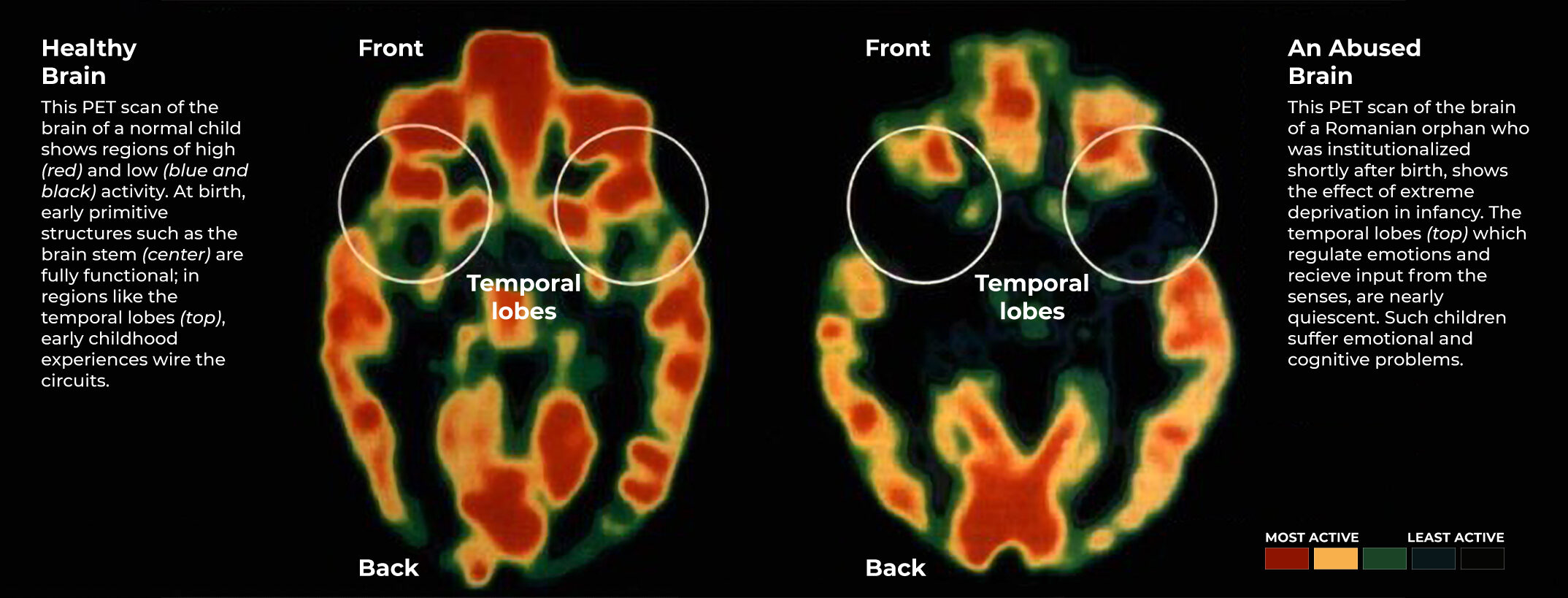

PET Scan Comparison of a healthy brain vs. an abused brain. (Chugani M.D, H. (n.d.) )

As an individual moves into adolescence, brain development changes to begin pruning out the least-used synapses. The brain connections begin to become more specific and as the brain matures, the brain becomes less dense. If the most used synapses are those that are more functionally basic, the portions of the brain that support social and emotional well-being fall behind and are potentially “pruned” out. This lessens a person’s ability to have the brain function in a way that supports emotional regulation and social connections, ultimately impacting lifelong positive mental health.

Recognizing the profound impact of this period of growth, educational institutions, particularly schools, play a pivotal role in fostering healthy growth and brain development. Schools and educators are tasked with creating educational environments that nurture positive interactions and stimulation during this crucial phase. A supportive ecosystem that addresses the well-being of the entire student, while collaborating closely with their caregivers, is fundamental for developing a strong social, emotional foundation that will serve the child into adulthood.

When focusing on schools, where many children spend much of their day, including during their early developmental years, these spaces can contribute to students’ mental health concerns in a variety of ways. In addition to stress and anxiety related to school performance, students can experience bullying, social difficulties, and discrimination (Marraccini, M. E., Pittleman, C., Griffard, M., Tow, A. C., Vanderburg, J. L., & Cruz, C. M., 2022). Additionally, as educators experience an increase in stress or their own mental health challenges, it can affect their ability to support students. Teacher stress correlates to unfavorable teaching practices, more conflicts with students, and less optimal student outcomes. “Early research on preschool disciplinary practices by Gilliam (2005) reported that the rate of expulsion from state-funded pre-K programs is three times higher than that for K–12 programs,” (Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs, 2021, p. 8). These higher rates at such an early stage of development have significant downstream implications as students’ progress into elementary and middle school.

While the demand for mental health services for students at the early childhood, elementary, middle school, and high school level is on the rise, so too are efforts to address the concerns. Schools are stepping up to the challenge of meeting students’ mental health needs by employing mental health service providers, typically school psychologists, counselors, social workers, and nurses. However, there are widely varying degrees of caseloads and expectations for individuals in these roles when compared across the U.S. Partnering with community-based providers is a strategy that can help address the issue of school staffing shortages. However, schedule coordination and communication are still barriers in ensuring students have access to these resources.

Offering mental health services within schools has demonstrated greater rates of success as compared to accessing services within their local communities. In the case of students who reside in rural areas of the country, schools may represent the only mental health resources for students. Research demonstrates that students who receive social–emotional, mental, and behavioral health support have greater academic success. School climate, classroom behavior, engagement in learning, and students’ sense of connectedness and well-being all improve as well (National Association of School Psychologists, 2021).

In our next installment in this series, Supporting Students to Thrive: Part 2, we will explore more of the innovative and thoughtful solutions schools are implementing to meet their students’ mental health needs, supporting development of the whole child to ensure the best long-term outcomes for each student.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Children’s Hospital Association. (2021, October 19). AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. https://www.aap.org/en/advocac...

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Youth Risk Behavior Survey, Data Summary & Trends Report 2009 – 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyou...

U.S. Department of Education. (2021) Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/...

Nelson, C.A. (2000). Human Brain Development [Digital chart]. Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvar...

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Fast Facts: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/violencepr...

PET Scan Comparison [Digital image] Dr. Harry Chugani M.D., Chief, Division of Pediatric Neurology, Directory, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Center, Children's Hospital of Michigan (n.d.)

Marraccini, M. E., Pittleman, C., Griffard, M., Tow, A. C., Vanderburg, J. L., & Cruz, C. M. (2022). Adolescent, parent, and provider perspectives on school-related influences of mental health in adolescents with suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. Journal of school psychology, 93, 98–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp....

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.go...

Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs (p. 99). (2021). U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/...

National Association of School Psychologists. (2021). Comprehensive School-Based Mental and Behavioral Health Services and School Psychologists [handout]. Author. https://www.nasponline.org/res...